Shikata ga nai: It cannot be helped.

Carl Watanabe is a Japanese American, an intelligent, thoughtful, fun, and earnest man. He has been in public radio and public life for many years. I first met him years ago in his public radio role. Once I realized that he and I shared WWII from very different perspectives — he was Japanese American and I am native Californian who lived on the San Francisco penninsula — I had to talk with him.

Carl is a 74 years old Californian, an American citizen who has done a life time of psychological and intellectual reflecting and studies around his early experience as a very young child in an assembly camp (his family of four lived in an 8 x 12 white washed horse stall at the Santa Anita Racetrack) and then in an Internment Camp in Arizona with his family — his young mother, his father and his four year old sister. Both his mother and his sister died in the camp which makes the whole experience even more indelible and difficult to leave behind, not that one ever leaves this experiences behind — they are the threads in the life tapestry. As I spent time with Carl one of the subjects we talked about was the experience of shame in the Japanese American community.

Carl is a 74 years old Californian, an American citizen who has done a life time of psychological and intellectual reflecting and studies around his early experience as a very young child in an assembly camp (his family of four lived in an 8 x 12 white washed horse stall at the Santa Anita Racetrack) and then in an Internment Camp in Arizona with his family — his young mother, his father and his four year old sister. Both his mother and his sister died in the camp which makes the whole experience even more indelible and difficult to leave behind, not that one ever leaves this experiences behind — they are the threads in the life tapestry. As I spent time with Carl one of the subjects we talked about was the experience of shame in the Japanese American community.

“Wait” I said,” shame is an experience that holds true across cultures and history when there is violence and particularly where there are strong tribal and community ties. The person who has survived violence will often feel shame. It is a common and shared experience in human beings.

Carl: ” I challenge you to be more nuanced in thinking and talking about shame. “

Me “OK, but Carl, please help. “

We exchanged emails on the subject. The most important musings on the subject were Carl’s.

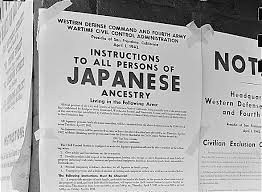

Here are some excerpts

Shame: The whole Japanese American community (1st generation immigrants from Japan who were still citizens of Japan, U.S. born American citizens, and the children of Nisei, such as me) was ashamed that the country, from which we emanated and were emotionally connected to, Japan, had attacked the country in which we now lived and loved. People like my father understood why the vast majority of America reacted the way it did to the attack on Pearl Harbor (concerning fear of Japanese people). Any attempts to view the event from a rational point of view were doomed to failure (e.g., that we personally had no connection to the fighting; and that we were American citizens (ironically all treated as aliens), imbued with constitutionally defined inalienable rights; and that Italian Americans and German Americans were, for the most part, spared the racism, anger and hatred. Thus, the adults felt helpless in protesting how we were being treated. We were ashamed that this happened, and even though we were not at fault, we had to shoulder the blame. That was inevitable.

There is also shame connected to being locked up and  incarcerated even though you know you’re innocent. Similarly, the shame of being evicted from your home, having to sell your belongings at bargain prices, at having your belongings being displayed on the street, etc. The shame and helplessness connected with not even being able to protect the lives of your pets and other animals.

incarcerated even though you know you’re innocent. Similarly, the shame of being evicted from your home, having to sell your belongings at bargain prices, at having your belongings being displayed on the street, etc. The shame and helplessness connected with not even being able to protect the lives of your pets and other animals.

Ultimately, for my father and his generation, the shame was also connected with having allowed this (the Incarceration) to happen.

I wrote Carl again and asked if I could publish this.

I’d forgotten that I’d written this. I’d been carrying these thoughts around for most of my life. The impact of being part of a group that had attacked our country had been pushed down within me and kept under the surface. Otherwise, I’d have become too bitter and self-absorbed with collective guilt that I’d be impossible to live with. It’s as if I had a box of forbidden memorabilia kept in an attic hideaway, rarely looked at, but always retained as I moved from house to house.

Yes, publish this.

Soon we will publish Carl’s search for a narrative different than the narrative of the dominant culture, his own and that of his people. This piece talks about Carl’s clarification of identity, meaning and yes, peace. Along with that, an interview with German’s who were also children during that time period.

Andrea Steffens