I first met Chris when I was volunteering at a refugee center. He talked about being frustrated with the lack of post resettlement services provided or in this case, not provided. There was something very special about this young man who was probably under 25 and was teaching ESL. When I met him instead of exercising interests like most of the young people I knew his age, he was mentally working on a vision for the refugees whose needs he saw were not being met. And what he came up with was clearly unusual, and truly great and ultimately successful concept. Mohawk Valley / Utica Community Center. A place where refugees could design and provide for their own needs. Chris finally located a lovely abandoned church which met the criteria for his vision and worked to turn it over to the refugees to put together something that addressed their real needs.

Through social media, I watched the work of MUCC grow into the lively and dynamic community of refugees running their world with lots of videos starring refugees running the show. They put on cultural events, celebrated holidays of a secular and spiritual nature, created tutoring programs for young people and events for older people in the community. They sang, they cooked, they ate and they flourished and somewhere in the background you could see Chris probably wearing a silly hat and laughing. All this began as the Chris Sunderline Magic Show where

Now he and his group can manifest just about Anything for Nothing — yes, they functioned totally without funding. They had zero, zed, zilch money. And by the way, something not usually mentioned in a bio of this sort is that Chris, in addition to all else, he is tremendous fun, never afraid to be silly and has a wild sense of humor all of which go with his Can-Do nature.

Additionally, he never gives up on anyone or quits working on their behalf — he build bridges for refugees into a larger community that is not always been excited about the presence of these newcomers.There is still the concern among citizens that refugees will drain the funds of social services. Chris and MUCC — Midtown Utica Community Center — provide most of the social services needed and in doing this has created a common-sense model of mutuality that could change the way services are provided in a larger world and in a way that builds strong communities where every one involved benefits.

And what do we think the young people learn about manifesting dreams whether it is going camping with carloads of friends or going to a prestigious university? They are learning as we all can that if we have a vision to which we hold passionately, there is probably a way to manifest it. Chris is also a pragmatist: He organized Celebrate Refugee Day so he could introduce refugees to a community not always excited about their presence. He shows how the refugees enrich their new small city that is Utica, USA. Oh and the food they bring. How much immigrants and refugees have added deliciously to the American diet. Chris, I say a cookbook is in order.

Incidentally, Chris teaches ESL in four different schools to earn a living for his family. He has made nothing from his work with refugees but I do believe that he deserves to make a living at something he is so good at. But for now, just let me introduce him.

Chris: Utica is one of the most diverse cities in the United States. When I graduated high school, we were the 4th most diverse high school in the nation. Oh and for the record, I am white, ethnically part Lebanese.

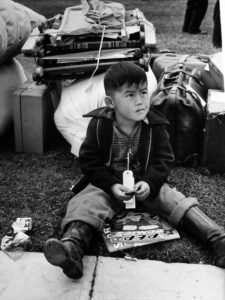

Utica has always had refugees and as my parents were far from rich, I lived in a diverse neighborhood which proves what integration was created to do: I am a product of this. Growing up I had friends from all different ethnic groups and socio economic backgrounds,many of whom were refugees. One of my best friends whom I first met in kindergarten was born here in Utica 2 months after her family arrived from Vietnam having fled for their lives. I learned early what an Immigrant is and what a refugee is and the difference between them.

I grew up knowing how to curse in 10 languages. I had eaten chicken and rice dishes from 5 continents and had knowledge of holy days and traditions that few kids from the white western world would ever encounter. This was MY America. This was MY normal.

When I went away to college I discovered how white America is and how limited were the experiences of my fellow students. How little they knew of other cultural traditions, foods and wonderful people. Most of my college classmates were not aware of the America I knew.

So create somewhat of a normal life for myself, I worked in a community center where I was the only non-black person. This helped my need for diversity and was my way of getting to center.

I would sometimes bring a kid or two up to the college to see what it was like. The looks from the students could kill. If anyone asked why I was with this person of color, I would lie and say it was a friend from high school visiting — my way to ease everyone’s discomfort.

When I returned home after graduating, I immediately started working at the adult learning center, a place to teach adult ESL to learners who recently arrived. This was new for me. I had never engaged with the adults of a refugee community except peripherally – I was always introduced to refugees though school and those who were already able to communicate and socialize with me.

So this was a whole new world that I embraced fully. I was 20 when I started and working with the adults and was often seen as their indispensable son who happened to be fluent in English. After school I entered a circus where my act was trapeze-ing from house to house helping with whatever was needed like landlord statements, locating food sources, helping fill in job applications, finding appropriate social services, transportation and all the sort. And why?

After the initial 90 day resettlement period, all support for refugee resettlement had dried up due to a cutoff of federal funding. So I tried filling this void and did as much as I could. The work was exhausting and never ending but in it I found how truly enormous MY family was and how grateful I was to have them. After my bland college days, the work had context which made it easier and so worthwhile. I acquired more brothers, sisters, nieces, and nephews, and grandparents in the last few years than anyone has ever had and there was a sense of deep deep satisfaction. Perhaps an instinctual memory of tribal culture for which I was wired. Who knows?

My approach seems to be different than most approaches to refugees — I think because of my early experiences in diversity I recognized the completely human presence in these new family members. Far too often for my taste, as I see them in social service settings,they’re referred to as clients, and that’s just not sufficient for me. It is so emotionally distancing — why are we afraid of getting close to our new coming people? As a result, the refugees existed separately in relationship to the larger community. After a few years of witnessing the creation of a post resettlement vacuum, I set out to develop a kind of agency, for want of a better word, maybe Refugee Community or something like that.

All I know is that my intention was to support my new family members talents and desires in a way that would lift us all up. I went searching for a building and after a bit, I found one and was allowed to claim it, And, ta da, the Midtown Utica Community Center was born as we took over an abandoned and beautiful old Episcopal church. In the first 3 months we clocked in over 3,000 hours of the buildings use.

Anything and everything that had been missing in the lives of refugees began happening at MUCC: there were variety of religious services from all different faith traditions. There were cultural events, after school programming, you name it, it’s happened and is happening at MUCC. We have no funding and no staff. MUCC is completely volunteer driven, mostly refugees — yes, there are skills talents and abilities and drive in our refugees so all the success of MUCC goes to the ambition and energy of the people who make it all happen and I am still involved as much as ever and delight in seeing what my family members create as they have taken control — the whole point of the endeavor. They know better than I do what they need. So as I suspected without even being conscious of it, is that when you accept and recognize the humanity in another, they do become family and that goes both ways. And when someone is family, you will do anything you can to lift them up. And as they are lifted up,we’re all lifted up and no one is left behind. Including me.

submitted by Andrea Steffens,

Executive Director of Ashlar Center for Narrative Arts.